The memory of the ghetto is seared into us. The trap, the noose, the erasure.

The destruction, the inquisition, the theft of freedom.

The isolation, the rupture of the umbilical cords of community and memory.

The pogrom, the thunder of human brutality, directed to your mere being.

The fear, the terror, the bone-deep obsession with protecting life and lineage, knowing that disappearance is always a possibility, a turn away.

The ghetto is so powerful because it is external and internal, visible and invisible. It is the wall, and it is the refusal to look beyond it.

The ghetto leaves its marks in far time: it stamps a ghetto view on a person. Epigenetic trauma is also a blow to the imagination.

In The Black Hole of Auschwitz, Primo Levi reflected: ‘Auschwitz is outside of us, but it is all around us, in the air. The plague has died away, but the infection still lingers and it would be foolish to deny it. Rejection of human solidarity, obtuse and cynical indifference to the suffering of others, abdication of the intellect and of moral sense to the principle of authority, and above all, at the root of everything, a sweeping tide of cowardice, a colossal cowardice which masks itself as warring virtue, love of country and faith in an idea.’

The ghetto represents segregation, separation, concrete distinction. The ghetto is a world of walls. A prison cell, shared.

In the ghetto view from outside, Jewishness - boxed and foreign - belongs outside of the non-Jewish world. In the ghetto view from inside, the non-Jewish world belongs outside of Jewishness.

How might, following Alexia Levy and Yonathan Listik’s prompts, a wall become a window? How might we escape the ghetto? How might we transcend its claustrophobic borders, knowing what Bayo Akomolafe remembers: that thinking outside of the box is how a box would think. It's one thing to jump over a fence; it’s another to dismantle the fences inside. It’s one thing for destruction to end; it’s another for self-destruction to cease.

Escaping the ghetto, whether now or centuries ago, is no easy task. But we are not alone. We have ancestrality - a living memory, a heritage of wisdom and soothingly subversive consciousness - to support us. Jewishness is many things, but its deepest core is made of questions. Life is a question the world poses. Our lives involve asking questions of the world around us, of those around us, of divinity itself. We are here to be radically questioning, to wrestle with The Name, to lovingly reckon with the limited infinity we can grasp.

We are here to ask. And we ask to aspire towards goodness. For many of our most crucial sages, from Hillel to Rabbi Akiva, the central teaching of the Torah is about mutuality and reciprocity: to not do to others what is hateful or harmful to you.

We are here to learn and stretch towards ethical horizons. Tikkun olam, the reparation of the world, or to borrow Yvette Shipman’s phrasing, the ‘repair-ations’ of the worlds we are part of. Achvat amim, the solidarity and love(s) between peoples. Tzedek, the fluid force of justice, a law like gravity. Tzelem elohim, the understanding of each being as a likeness of divinity. Shalom, wholeness, a peace that pervades. Zakhor, to remember, to struggle against forgetting. We are here to take these principles seriously.

We are, like all peoples, the descendants of prophetic figures. Through ritual, we are invited to recall, nurture and apply what Heschel called ‘prophetic consciousness’. A practice of bearing witness, and refusing to normalise injustice, ‘a deathblow to existence’ in Heschel’s words.

It is these indispensable rememberings that have associated Jewishness over generations with radical inquiry, deviant resistance to empire, the protection of non-conformity, and the unravelling of oppression.

There’s a question, one of many, we should ask more of each other: what histories did you grow up with?

I was raised on stories of the Khurbn and the furies around it from an early age. The Khurbn (also known as Shoah or Holocaust) has been perhaps my closest political teacher. It has grounded me in the abyss of human cruelty, and forced me to live suspicious of supremacies, nationalisms, certainties, and fascisms. It continues to surprise and confound me, revealing simultaneously both the absurd love and profound brutality beings are capable of. Much of my life has been dedicated to studying, and G-d willing, trying to protect the memory of those it concealed.

Every year I peer into the catastrophic nightmare of the Khurbn, I am reminded more of how little I know. Horror destabilises. Hope looks. The cycle repeats.

I write Khurbn purposefully, for it is the Yiddish term for the Holocaust, the category-less haunting of the 1930s-1940s. Khurbn means destruction, and the word itself braids the most recent Khurbn with all previous destructions across history, for the Jewish people and others. The word itself refuses to isolate a person; it connects a person to a shared peoplehood of sufferings. It also reminds us of the deep collective and cultural wounds of trauma, and of the severe blow dealt by the Holocaust to Yiddishkeit.

When I mention to people that I’m passionate about Khurbn education, a common response is: ‘oh, we covered that at school’. But you can’t ever cover an infinite abyss, a glaring erasure. The memory of the Khurbn - like the echo of every atrocity, of every colonial crime - spills over any container. I can barely fathom the brutalities and fires that continually visited my grandmother’s small shtetl (rural community) in southern Belarus over decades. I still barely understand her pain - how can I ever assume to comprehend the horrors that enflamed tens of thousands of communities?

The Khurbn is one of the most searing indictments of ‘Western civilization’, racism and colonial logics. And that is precisely why Holocaust pedagogy has been sanitized and whitewashed. Radical Jewish memory, like the counter-colonial memory revitalised across diverse ancestral lineages, is dangerous.

A few years ago, in the book The End of Jewish Modernity, historian Enzo Traverso warned: ‘Institutionalized and neutralized, the memory of the Holocaust thus risks becoming the moral sanction for a Western memory: the civil religion of the holocaust order that perpetuates oppression and injustice. Jewish modernity put an end to the liturgy of the memory of traditional Jewish communities and heralded an epoch of liberatory struggles inscribed in history – a common history. This modernity was obliterated in Auschwitz; the civil religion of the Holocaust is simply its epitaph.’

There is much to unpack here, more than this essay can aspire towards, but let me note one thing. Traverso - along with many other historians of colonial violence - draw our attention to an under-looked dimension of destruction: epistemicide. The demolition of communal knowledges, trajectories and ethical compasses.

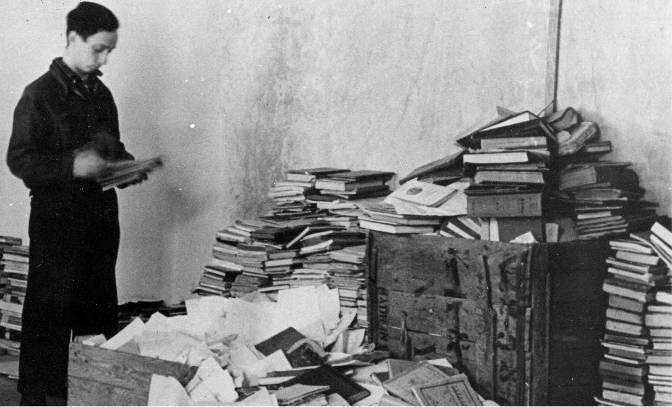

Without them, it is very hard to escape a ghetto worldview, a wounded gaze in the shadow of peoplecide. A ghetto worldview disastrously conceals history. That’s exactly why Jewish memory-keepers, from the depths of the ghetto and days before being deported to death camps, buried the stories of their communities in the earth underneath the ghetto. For our pasts to be seeds. For the rubble to be only a temporary sarcophagus. For the overwhelming memory of victimhood not to smother millenia of transformation.

It is precisely due to their efforts that I write, that I breathe and bend my ear, asking what the ancestors would think of us, what they would want from us.

As we try to listen, I can’t help but hear others also trying to listen and remember in a world of shadows. The Maafa, the Porajmos, the Nakba, the Sayfo, the Tsitsekun, the. Trace the globe with a finger, as Warsan Shire invites, and the entire atlas cries. Our world is a landscape of thickening wounds, inflicted by mentalities of devouring (porrajmos) and destruction (khurbn).

The mentalities of devouring and destruction haven’t gone away. Today, they are barely confinable; they’re planetary.

How to speak amid the shrillness of horrors? What to write when grief pulls you towards impotence? How to write when the moment demands you to be relevant rather than right?

I wish I had the superpower to write in languages customised to the receptivities and vocabularies of each person, to compel the diversities I know towards liberation for all the sacred peoples and lands between the river and the sea, the sacred lands between every river and every sea. If I could, I’d send sensoriums and poems and pamphlets to everyone I know, inviting us to grieve, envision, and stand together.

To friends and loved ones seeing Jewishness purely through a Eurocentrist paradigm, through Christian readings of what ‘religion’ is, through the omissions of nationalisms, through the muddled categories of ‘Western civilization’ or ‘Judeo-Christianity’, I’d invite them to dream differently, in dialogue. I want to spell a Jewishness that emboldens and heals. Jewishness, as an ecology of doings and traditions, has been about resisting empire and oppression for millenia; it is a source of reparative wisdom, and I would humbly argue, an indispensable accomplice for the times ahead. Ailton Krenak reminds us that memory is our ‘critical conscience’. Diaspora Jewishness as Traverso recalls has historically been the memorious ‘critical conscience of the Western world’; much more can be said too about the radical influence of Jews across Eurasia, the Middle East, and so many territories. Revisiting our histories, with their twists and paradoxes, can surprise us into new possibilities. As Palestinian socialist Issam Aruri reflects, ‘'Palestine was one of the first Arab countries with socialist ideas, and ironically they first came through early waves of Jewish immigration, starting in the late nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century.'

There are so many reasons why we are where we are today; far wiser and memorious people that can enumerate that history. I just don’t want us to lose sight of crimes that were committed against our imaginations. Following Traverso, we are here in some part because the Khurbn torched the communities that had forged other ways of being; taking advantage of the ‘silence’ of the erased, many power structures conveniently shaped Holocaust memory into a ‘mechanism of domination’. Yet we are commanded as Jews in our tradition to remember, to remember assiduously against the forces of forgetting.

To close Jewish loved ones, I want to invite you to be more Jewish than ever: to retain presence and openness and courage even when the hardest questions are asked of us. Pikuach nefesh, tikkun olam, tzelem elohim - these principles live in action, not just recitation. Many of us feel alone and crave elderhood. We can invite each other to be grounded by the challenges and balms of great teachers from across our deep Jewish time (Rabbi Tamares, the old rabbi of Mileiezyc has felt particularly prescient).

To my nationalist friends, who are called to love and stand behind ‘our people’. James Baldwin wisely challenged our notions of love: ‘if I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don't see.’ To rise to that challenge of love, we cannot look away, even from what hurts. It is easier to believe a nightmare is just that. But when a nightmare is reality, it has to be named and awoken to.

As I write, fascists, yes Jewish fascists and extremists, are in charge of a state. And they have been for far longer than many of us want to admit. Their politics is the politics of accumulation, vengeance and supremacy. Their understanding of ‘safety’ and ‘self-determination’ is one achieved by bombs, expulsions, orchard burnings and home demolitions. It is one where Palestinians must submit to brutal inequality, clearance and injustice. It is one that can never achieve the supposed safety it proclaims.

Their vision - rooted in negating the Jewish diaspora, devaluing Palestinian life, and accepting militarised Jewish life as collateral for expansionist colonia list dreams- has been costing Jewish communities from Israel to Poland to Morocco dearly for over a century. (Here’s Henryk Erlich and Simon Dubnow exchanging letters about it in the 1930s).

To those who still find orientation and salvageable promise in European political Zionism, I implore you to listen, even if only to the words of your chosen elders, such as A.D Gordon, a key spiritual influence on the early 20th century Zionist movement. In Mibachutz, written before the 1920s, Gordon writes: ‘Our relations to the Arabs must rest on cosmic foundations. Our attitude toward them must be one of humanity, of moral courage which remains on the highest plane, even if the behavior of the other side is not all that is desired. Indeed their hostility is all the more a reason for our humanity.’

To friends seeing silence or uncritical support of Israel as an adequate response to centuries of antisemitism, I urge you to not be naive. As the writer Yassin al-haj Saleh notes, many cloak their antisemitism through a “blind support of Israel. And they support Israel because it kills Palestinians and Arabs, the ones they themselves hate, not because they really care about Jews and their human dignity, or because they refuse discrimination against them. The logic of progressives a la Habermas way in Germany can be nutshelled in Orwellian terms: all lives are equal, but some lives are more equal.”

To those minimising any brutality, even the brutality that doesn’t fit the neatness of our most comfortable political prism, I don’t know what to say. To friends unable to even acknowledge the horrors of October 7th, I’m not sure what to say. To those unable to even acknowledge the horrors every day and hour since, I’m not sure what to say.

The Kotzker Rebbe reminds us that ‘nothing is as whole as a broken heart’. To be broken before all this, to be shaken, is a sign of health. Let us break in grief, for only then can we mend.

Do we live in a world of walls or mirrors?

The ghetto is a landscape of ruptures and severings. The worldview its imprints is overwhelming. There is little space for much else beyond survival.

Do we really want to be complicit in the violent imposition of our collective nightmares: ghettos, inquisitions and killings? As Dana El Kurd writes, ‘The irony of a state formed as the “antithesis” to the ghetto using ghettoization as a strategy of control is not lost on Palestinians.’

The visions of Ben-Gvir, Smotrich and company are of a totalitarian ethnostate, accomplished through dispossession, expulsion and killing. This is not a pipe-dream but a project, and they are working on implementing it right now. They are cooperating with others across the world, intent on the same in their own contexts. Our response can’t be to acquiesce to fascism and its ghettos of thought and possibility - it’s to refuse, escape, and resist.

Every wall can also be seen as a mirror. And so they are. Whether it be Indigenous peoples from Turtle Island to Abya Yala, radical Afro-diasporic thinkers across the Caribbean, anti-apartheid activists in South Africa, or Ukrainians resisting aerial bombardment, so many across the peripheries of our planet see themselves and their own struggles in Gaza, in the West Bank, in the cries from Be’eri. And so do many Jews. I personally cannot watch videos of people fleeing their homes, of children screaming in despair, without feel-thinking of my grandparents’ stories.

Mirrors threaten those who don’t want to look. Avot Yeshurun was an acclaimed poet who wrote in modern Hebrew. Although he emigrated to Israel in the 1920s, his family remained in Poland, and was murdered in Belzec in 1942. In 1952, reflecting on the Khurbn’s vicious aftershadow, he couldn’t help but name the Nakba in conversation. “The two gaze directly into one another's face”, he said.

A mirror only threatens those who don’t want to look. Just days ago, Yeshurun’s words echoed in the writings of Israeli journalist Israel Frey, who lamented a collective indifference to the pain of others, and reflected on the moral trap of demanding recognition without offering it. As Frey suggests, without reciprocity, we end up becoming a ‘mirror image of everything we dislike.’

Across the world, we are facing staggering expressions of violence. Democidal, politicidal and genocidal wars from Sudan to Myanmar to Palestine to Ukraine to Tigray. Macro-criminality from Russia to Mexico to Nigeria. Corporate violence, from London to Frankfurt to New York to Abu Dhabi to Hong Kong. Border violence, from the Mediterranean to the Caribbean to the Pacific. From all angles, the spiraling and overwhelming violence of the climate crisis.

There are those who want a world of inequalities: a world of walls, extractions and extortions. And there are those dreaming against this, and believing in a world where life - the sanctity and necessity of life for all - is valuable.

With the climatic odds we’re up against, there is simply no route to individual or group safety of any kind that doesn’t involve us radically relying on each other. Supremacy and inequality guarantee our unsafety. Only by challenging them can we open the space for at least something different.

We urgently need to encounter each other, to meet like converging waters, following Denise Ferreira da Silva. Nêgo Bispo, an elder of blessed memory, urged us until his recent day of departure towards confluence. Observing the ways river meet, Bispo taught that when a river encounters another river, they don’t stop being different rivers, they confluence into a stronger one. How might a confluence of peoples, of knowledges, emerge?

We need to dream, to renew, and build through the horror. To imagine collective safeties as intertwined. And we need each other to remember our dreams.

A close Lebanese-Palestinian friend Joey Ayoub offers a touching invitation:

‘I'm hoping that this is also the beginning of a renewal in Jewish radicalism. It was murdered - along with most of Yiddish culture - between the Holocaust, Stalin and integrationism/Zionism but there's a revival already happening, and it would be interesting to see how this revival can meet the challenges of a new Israel that's much more Mizrahi than it was when the main debates in Jewish politics in Europe were between Zionism and Bundism (and much in-between).’

There is such generosity in dreaming for another.

The world is painfully vast and unjust, and sometimes all I pray for is for all of us to elude and dismantle the ghettos. The ghettos inside of me are powerful.

Luckily, there are locks. Luckily, the key is in the hands of the Other.

Epilogue - an after prayer

There are so many omissions in this piece. I type any word and think of every word I’m not. I can’t possibly do justice to what the wounds and destruction in Khan Younis, in Gaza City, in Kfar Aza, across so many families, mean. I write with fear, knowing that people I love may interpret any utterance from a reading of fear.

But with all the flaws, I write from a place of love, and that’s the final prayer I want to leave. I mention love because it’s probably the most consistent omission in this piece. Ghettos - the architecture of empire - are tremendously powerful, but inevitably vulnerable, and especially vulnerable to love.

Marek Edelman, a leader and survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, reflected: ‘People [in the ghetto] were drawn to one another as never before, as never in normal life...This is something people still don’t know or don’t understand, and that’s why it’s so important to point it out – that if you are capable of love, if you love, you will remain a normal person even in the most horrid circumstances.’

May we all find our ways towards radical love in these times.

i love you and your writing!