Summer, 1942. Warsaw is under Nazi occupation. For years, the city’s Jews have been imprisoned, surveilled, policed and starved, confined to the ghetto.

In the shadows, the Oyneg Shabbes collective, coordinated by historian Emmanuel Ringelblum, documents life in the ghetto and Nazi crimes. Meeting regularly in clandestine encounters on the Sabbath, this collective of collaborators includes scientists, social workers, teachers, and a rabbi, who together assemble a sprawling archive. Converging across their political differences, they compile essays, diaries, songs, folk histories of Jewish villages, works by eminent rabbis, clips from dozens of the ghetto’s underground newspapers, comics, ration cards, theatre programmes, photographs, and children’s drawings. They conduct surveys, investigate the plight of Jews in rural areas and other countries, and encourage fellow ghetto residents to put their memoirs to paper. As months go by, the collectors add horrifying reports about massacres, executions and deportations into the archives.

This radical commitment to testimony and memory protection wasn’t unique to Oyneg Shabbes, but found across many communities under occupation. Hundreds of kilometres away in Vilno, the ‘Jerusalem of Lithuania’, the ‘Paper Brigade’ smuggled thousands of historic Jewish texts into the ghetto and buried them, avoiding their destruction by Nazis.

On 22 July 1942, mass deportations from the Warsaw ghetto to the death camp in Treblinka begin. Knowing what awaits them, Oyneg Shabbes carefully begin to place part of the archive - referred to as ‘the treasure’ - into metal boxes and milk canisters, and bury these in locations around the Ghetto. Between July and August, the first ten metal boxes are buried in the basement of a school.

That summer 254,000 ghetto residents - including many members of Oyneg Shabbes - are deported to Treblinka and murdered. Only 70,000 people survive in the ghetto. The remaining archivists continue the work. Some escapees from death camps, such as Yakov Avraham Krzepicki, return to the ghetto and add their testimonies of the unspeakable horror into the forest of paper.

In January, another mass action to deport and kill Jews begins. In February 1943, the last members of Oyneg Shabbes bury the final set of metal cans under the earth of Warsaw. On one page, torn from a schoolbook, 19-year-old Dawid Graber writes: “what we were not able to pass through our cries and screams, we hid underground.”

Just three months later, as Nazi troops enter the ghetto, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising erupts, with hundreds of Jews taking up arms and resisting. Multiple Oyneg Shabbes members participate in the Jewish Combat Organization (JCO) and are killed. After weeks of fighting, by mid-May, the ghetto is destroyed.

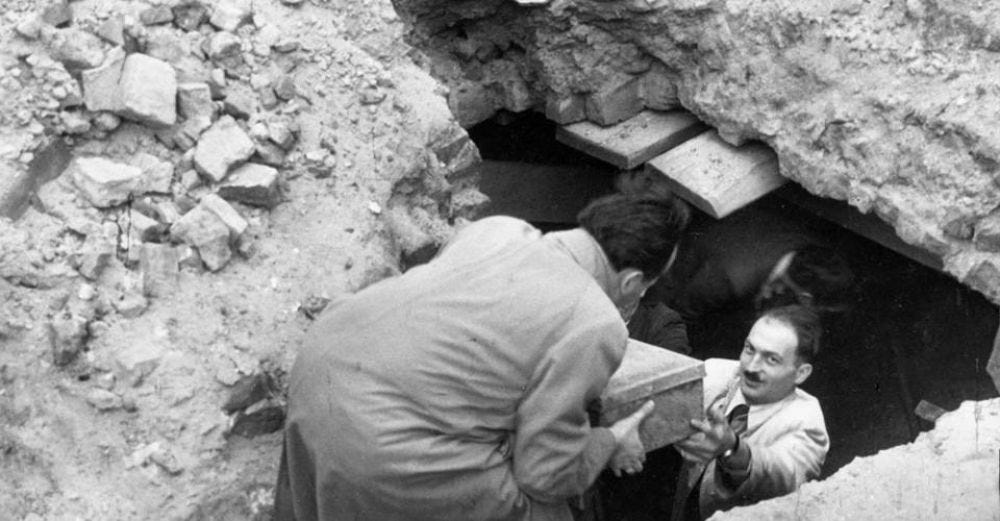

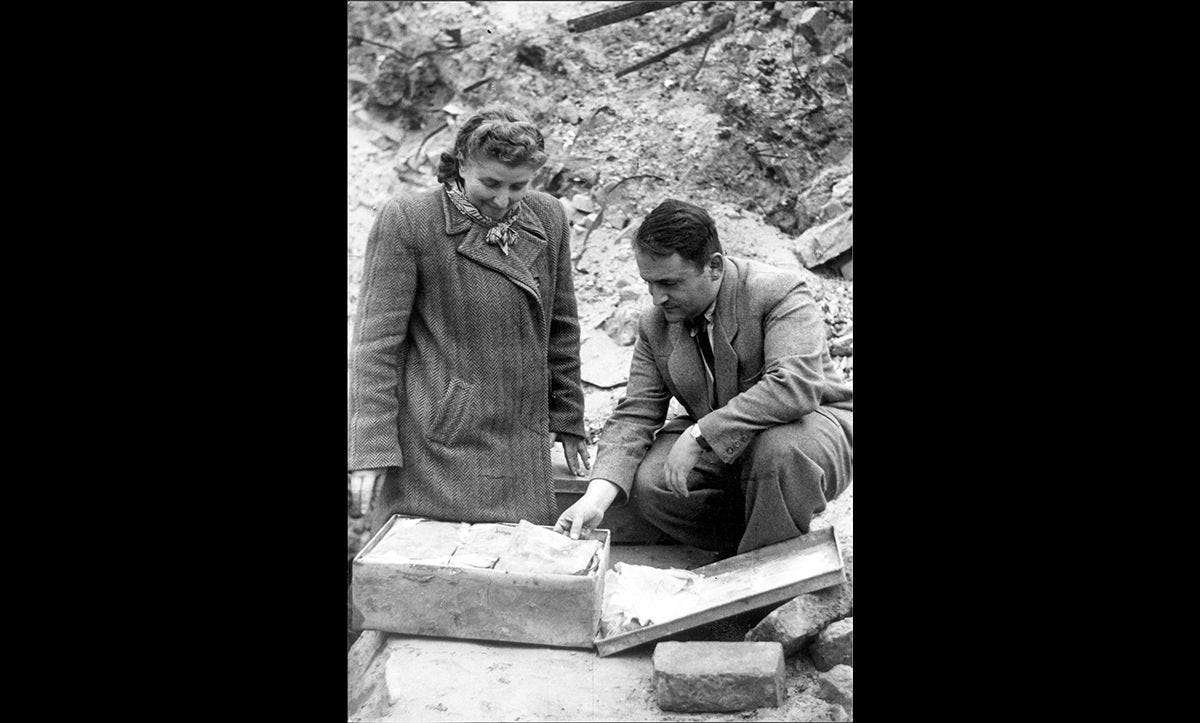

In 1946, amid collapsed buildings and rubble, the first metal boxes buried by Oyneg Shabbes are found. In 1950, the next cache is unearthed. The last part of the archive remains missing.

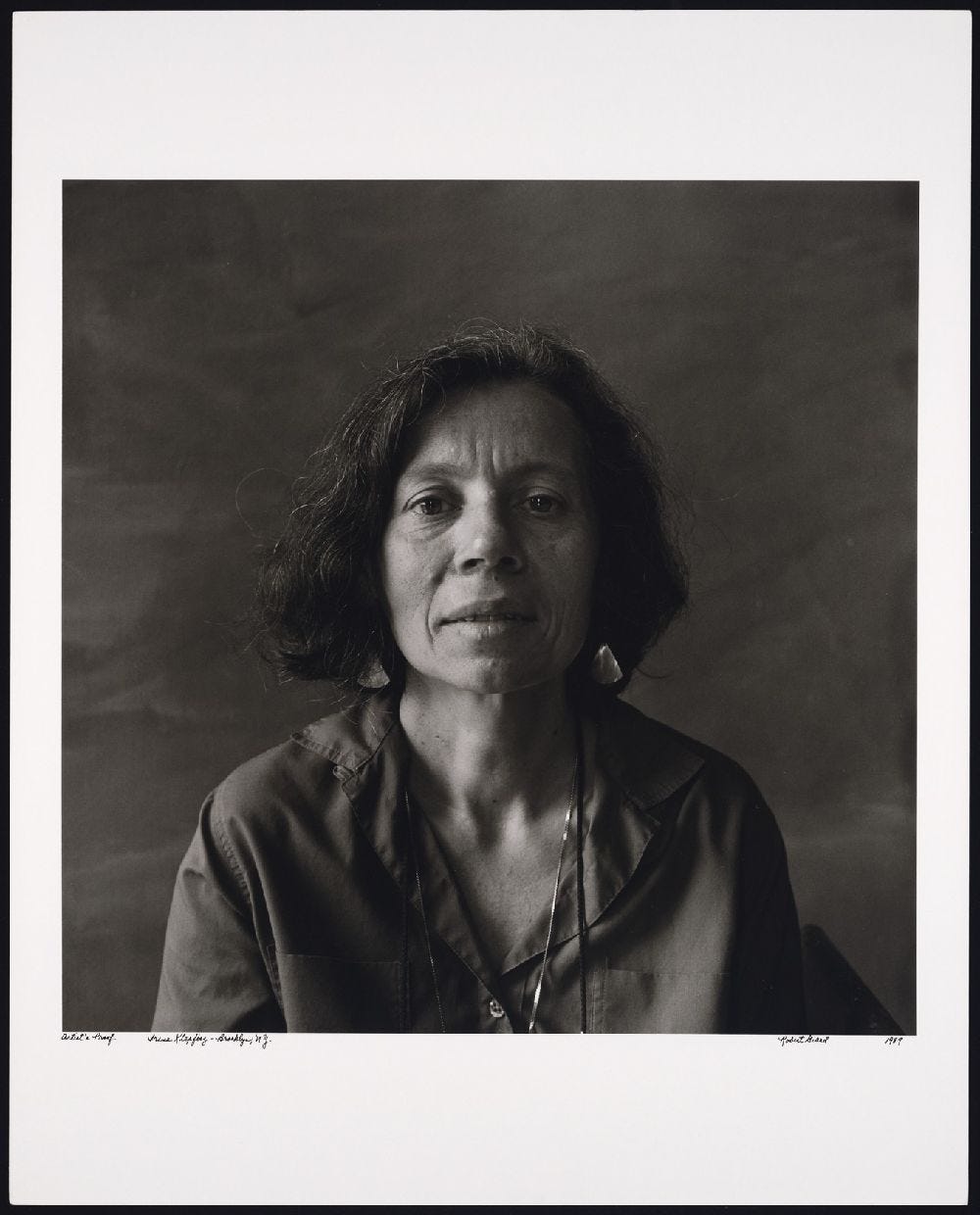

Winter, the first weeks of 1943. Another radical act of protection and loving subversion takes place in the Warsaw Ghetto. Irena, the one-year-old daughter of Rose and Michał Klepfisz, escapes with her mother into the Polish countryside. Irena and Rose survive the war and move to the United States, where Irena would grow into one of the most beloved poets, activists and Yiddishists of our era.

In her beautiful poems and writings, languages marry and transform in mutual love, Yiddish braids into English, and what is mis-named as lost is breathed into the future.

In 2019, Klepfisz is invited to speak on a panel in New York, reflecting on the legacies of Bundism and Jewish radicalism. She opens her remarks, citing the historian Samuel Kassow, who has devoted many years of research to the Oyneg Shabbes archive and the biography of its founder, Emanuel Ringelblum.

‘Over time Ringelblum realized more and more clearly that the survivor identity would overshadow the prewar past. The “before” would be erased by the “after.” As he confronted the unfolding disaster he fought all the harder to preserve the “Now” and the “Before,” to keep the a posteriori label of “victim” from effacing who the Jews were before the war. In a very real sense [Ringelblum] saw history as an antidote to a memory of catastrophe which, however well intentioned, would subsume what had been into what had been destroyed.’

To protect the ‘Before’ before the swallowing of the ‘After’. To turn, to return in search of ancestral expansiveness in times of colonial constriction.

The world(s) over, so many elders, collectives, initiatives and communities practice the sacred work of memory keeping, of unforgetting, of revitalizing past practices and perspectives that may help remedy the unraveling wounds of the now.

One group that has reverberated through my feel-thinking is the wonderful Cave Bureau collective in Kenya, which works on architecture for an ‘age of trauma, resistance and healing.’ Directed and founded by Stella Mutegi and Kabage Karanja, they describe their offerings as ‘remedial acts of Reverse Futurism’: ‘means to return our imagination in time to look at ways to dismantle present-day trauma and dysfunctions borne from our imperial and colonial past.’

Their work, in its gaze-stretching range, emanates this approach of ‘creative retrospection’, looking backwards-forwards, seeking to confront past traumas through ‘projects of healing that are inclusive for all life on earth to thrive’. Their ‘Steam Harvester’ design for example, amplifies the communal technology of the Mount Suswa Maasai, harvesting steam from vents in times of drought. Rather than inadequately summarising and diminishing their work, I prefer to simply leave doors to their propositions: Freedom Forest, The Benevolent Reparations Institute, Slave Caves.

Drawing inspiration from decolonial readings of ecologies, geologies and legacies of resistance, Cave Bureau build ‘microcosms of repair’ against an ‘Anthropocene’ that needs to be ‘drastically thinned out and shortened’.

In a manifesto they write, ‘Without exaggeration or prejudice, we can say that a few white men saw it fit to divide the world, grossly claiming it for themselves, all the while extracting all manner of resources by any polluting means necessary, be it human, animal, plant, or mineral in form. A trend that arguably still pervades the world today, having permutated into the neoliberalist order of our times, with new superpowers at play. As Lesley Lokko says, the world is usually organised according to principles that flatter the dominant imagination. The painful legacy of trauma inflicted on indigenous citizens of the global south, as well as some from the north, has manifested itself across many lives, through many villages, towns, cities, and ecosystems across the planet.’

Against this traumatic flattening of imaginations, their reimainings speak ‘towards green pathways of healing, where the natural environment and the cities converge to create a restorative artifice within landscapes of phantasmagoria in Nairobi. Like many cities around the world, this is a city in need of grander interventions of restoration to redefine the more-than-human city of the future.’ After all, we can do far more than maintain cities of forgetting, 'where monuments of broken bodies in stone and oxidised steel keep you in silence as you walk by to lament over vestiges of past crimes and perpetuated prejudices that appear to be stuck in time and are disjointed from the climate crisis, even though they are ultimately one and the same thing.’

Cave Bureau echo the questions of Saidiya Hartman who asks, ‘If it is no longer sufficient to expose the scandal, then how might it be possible to generate a different set of descriptions from this archive? To imagine what could have been? To envision a free state from this order of statements?’

The Indigenous Krenak philosopher Ailton Krenak speaks of futuro ancestral, ‘ancestral future’. A paradox, a parachute for our times.

For Krenak, how we understand time, timing and tempo is indispensable. European coloniserss used a rigid, linear narrative of past-present-future to justify their invasion of the world. The story of progress was cemented as a core purpose of society, motivating accumulation, voracious economic growth, and constant extractivism. Against such a totalising story, protecting and valuing ancestrality - the teachings, wisdom, and practices of those before us - is a way of ‘putting a brake on violence’, gathering our bearings, and recovering memory, ‘our critical consience.’

In Krenak’s embroidered retellings (which constantly quote the reflections of Davi Kopenawa Yanomami and Yanomami cosmology), ancestrality is a buffer, a pause, a weapon, a clarifying reminder. Most of us live in a pervasive culture of commodity, where everything is perceived as a commodity, and every commodity has an expiry date. In capitalist cosmology, what is past has passed and is no longer relevant. Valuing ancestrality immediately challenges the linear jurisdiction of importance.

Ancestral knowledge in Krenak’s descriptions isn’t just a body of static ideas from our ancestors (whoever we may consider them to be); ancestral knowledge includes ecologies, approaches, institutions, and ways of being in the world, such as dreaming. As he says, ‘We are globally 8 billion people that no longer dream in this world, and the world ends up being a nightmare.’ Recovering the capacity to dream is also remembering that ‘all the things that humans are capable of configuring and imagining, are born first in dreams.’

Reconnecting with ancestrality also requires reckoning with key timebound ideas in our societies, such as the idea of eternity. For Krenak, ‘the only thing that is eternal is life.’ He cites the Kaxinawá word or ideogram xukuxukuê, meaning: ‘life always’. Translating xukuxukuê, Krenak describes this as a principle that applies to what in Western terms is called ‘nature’, rather than us humans or other individual species. We humans, like other species or expressions of life, are compost or adobe or earth, being and dying in cycles. We can be better understood, in Krenak’s phrasing, as ‘humus sapiens’.

Yet contemporary Western culture finds deep discomfort in human mortality, finitude and cycliclity. This discomfort reveals itself particularly in our relationship to the preservation of human culture. Krenak, while valuing the medium of text, looks askance at an insatiable written culture obsessed with eternifying everything. As he says, ‘[The white man] notes everything, registers everything because he has a thinking full of forgettings. It’s an absurd phrase. That which should be eternal is filled with holes. A thinking full of holes will lead us to be filled with holes.’

To approach ancestral futures for Krenak is about bursting open our senses of hope; not searching for a ‘placebo hope’, but cultivating hope-senses grounded in our experience and receptiveness to the world. For Krenak, a placebo hope imbues passivity in us: ‘everything will be okay’, ‘you don’t have to worry or do anything’, ‘technologists will solve the climate crisis’, ‘artificial intelligence will decipher verything’. ‘Placebo hope’ alienates our particular ability to be in the world, asking us to renounce our uniqueness.

Ancestral futurism, following Krenak, starts with simply remembering that our ancestors, whether closer or further in our family trees, knew something about how to inhabit this world of limits in balance with other beings. They were in this earthly existence, and found - in their own ways and to varying degrees - contenment, splendour, gratitude and celebration in it.

Furthermore, re-embracing ancestral thinking isn’t simply a case of ‘going backwards’, it’s far wider and deeper. It involves understanding ancestry as vertical and horizontal, lateral and circular, because ancestry in the broadest sense is ecological. As Krenak explains, ‘When we say that the future is ancestral, it has more to do with DNA than with genealogy. That’s the worldview: it’s the ability to go back to an event that created the world and that is alive in you. We want a constant creation of everything and of ourselves. This is what happens in the DNA, this code passed on by our ancestors. This can reintroduce us into the constellation of life within the planet, where we stop being an expert and realise we have a common origin.’

In this worldview, ancestrality returns us to our role as beings of the Earth, experiencing a reality of xukuxukuê - where existence, water and time flow through us, and continue. For Krenak, when we heal our separation from ‘nature’, we ease the fear of death. If we are a part of life, that is eternal, there is no death only metamorphosis and transformation.

Ancestrality reconnects us to what we never left, just forgot.

'In our mother's womb, we are all the futures that supersede this culture.' - Orland Bishop

In his seminal work on Quilombolismo, the Afro-Brazilian polymath-activist-artist-poetician Abdias Nascimiento starts with a sharp call to remember: ‘Black Brazilians urgently need to recover their memory. This has been systematically attacked by the structure of power and domination for almost 500 years. The same thing has happened to the memory of black Africans, who are victims, if not of serious distortions, of the most crass denial of their historical past.’

Memory for Nascimiento was indispensable because it was the basis of the future. As he writes, for black Brazilians, ‘to have a past is to have a consequent responsibility in the destinies and future of the black African nation, even while preserving our status as builders of this country and genuine citizens of Brazil.’

As part of this memorious invitation to commit to the future, Nascimiento called on Black Brazilians to ‘edify the historical-humanist science of quilombolismo’. Quilombos were and remain communities established by escaped enslaved Africans, often deep in the forest. These were, in the words of Ciro Flamarion, ‘breaches in the slavocratic system', direct resistances to the haunting colonial violence of genocide and enslavement.

As Nascimiento writes, the ethical foundation of quilombismo was about ‘ensuring the human condition of Afro-Brazilian masses’. Rooted in conviviality, solidarity and shared existence, quilombolas enacted a model of economic egalitarianism. Property was collective, and quilombolas aimed to be creative societies where work was not defined as ‘a form of punishment’ or oppression, but rather as a shape of ‘human liberation’. For historian Beatriz Nascimento, quoted by Abdias, quilombos were-are spaces where ‘liberty was practiced’ and ‘ethnic and ancestral ties were reinvigorated’, playing a huge role in the creation of ‘black historical consciousness.’

Abdias de Nascimiento saw quilombismo as an ‘idea-force’, ‘an energy inspiring models of dynamic organization since the 15th century’, an affirmative archive to root Afro-Brazilian culture in times of oppressive amnesia.

The writer and curator Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung offers an expansive reading of quilombismo, as ‘the long history of remonstrations and revolts against dehumanization of the people of the world by the people of the world.’ In Berlin, he recently curated the stunning exhibition and cultural series named ‘O Quilombismo: Of Resisting and Insisting. Of Flight as Fight. Of Other Democratic Egalitarian Political Philosophies’, using Abdias Nascimiento’s work as a departure point to weave together dialogues about liberation and fugitive freedom across the world.

For Bejeng Ndikung quilombismo is ‘an invitation to accompany and dwell in these psychic and physical spaces of the detour - to embody the discontinuity of narratives, to delve into the ravines and the back of the mountains, to explore the physical and metaphorical spaces of the camouflage, of disguise, and of fugitivity, past and present. This invitation imagines what cultural resistance of our contemporary condition(s) could be, and how this might be informed by the cultural resistances and empancipation schemes of the past.’

As Soh Bejeng Ndikung hints, the story of quilombismo is a spiral story, where endings and beginnings can switch positions, and lose their linearity. In such stories, pasts are always present, sometimes ahead of us, looking up at the futures it can old.

How do we remember? As we voyage into the oceanic darkness of the past, where do we point our lanterns towards? How can we stay alert to the traps and reductions of recollection (the coldness of statistics, misreading the present into the past, assuming discontinuity), and how might we remember in more vivifying ways, that heal wounds and compel us towards life?

From a very young age, I was exposed to many stories about the Khurbn (Holocaust, Shoah) and the Second World War. These stories - choked with silence and omission and unknowing - would be later coloured and reshaped through watching dozens of films and documentaries, that helped detail the arson that burnt an abyss into the ecological fabric of ‘Europe’. But the amorphous, infinite and unnarrable loss of any collective trauma overwhelms any word that tries to contain it, any statistics that summarise, any film that edits chaos into plot. The more I learn, the more I notice the water-like immensity of memory. Loss, to be loss, exceeds.

To process loss, we often seek to compress it, forgetting that what we reduce reduces us in the process.

When we talk about genocide, we often miss its ecological and relational dimension. Unpseakable horrors don’t just steal lives, but entire ways of being, languages, relationships, jokes, geographies, libraries, medicines, forests.

The Yiddish poet H. Leivick asked, in an introductory essay to a compilation of songs recovered from ghettos and camps in 1948: ‘Should we not eulogize murdered songs as well as lives? Should we not hold memorial services for the souls of words, of songs, of rhymes, which together with the lips that uttered them were destroyed by fire or in the gas chamber? Yes, we must also say Yizkor for murdered folksongs, that we should hold the more sacred those which were rescued. Through them, their authors shall forever remain in our thoughts, though we may not know their names.’

Memory is life. What we remember is also what we enliven. Too often, the memory of genocide and erasure focuses disproportionately on the perpetrators and on the acts of killing. But in doing so, it ruptures our capacity for ancestral futurism, for drawing living inspiration from possibilities and practices that ancestors held close.

For me, one of the most powerful films about the Holocaust predates it. The film is ‘Mir Kumen On’ (We are Coming), a documentary film from 1935 about the Medem Sanatorium, a revolutionary educational and clinical facility for children and young people at risk for tuberculosis. Funded by labour movements, this self-organised center offered the highest quality care for the most vulnerable children from Jewish slums across Poland. The sanatorium emphasised emancipatory education, high-quality nutrition, spiritual support through community, and time in nature. Children were not just patients - they were encouraged to be researchers, artists, food-growers, writers and organisers.

The film lovingly assembles fragments of life at the sanatorium, from meetings of the children’s council, to songs and puppet shows.

In 1942, the Nazis deported over 200 children staying at the Medem Sanatorium, along with the teachers, nurses, and doctors that had cared for them, to be gassed in Treblinka. Loss, to be loss, exceeds.

Memory is life.

Samuel Kassow, the historian of Oyneg Shabbes, said that the collective did their work, despite the horror awaiting them, because they wanted ‘posterity to remember them from Jewish and not just German sources. As long as we control how we are remembered, you haven’t killed us.’

What we remember is what we let live. The future is and will be ancestral. The past is an archive of seeds. Under the earth of Warsaw, some of it is still missing, some of it is still dreaming the future.